Recently, there has been a major controversy in Armenia over a proposal to build a statue of the Soviet statesman and Bolshevik revolutionary Anastas Mikoyan in Yerevan.

Some Armenians regard Mikoyan as a remnant of the country’s Soviet past from which they want to move beyond. Others ponder possible political motives behind this sudden proposal. Why is there a sudden effort to build a Mikoyan statue now? There was never a statue of Mikoyan in Yerevan before. Some believe that it is connected with Armenia’s recent decision to join the Moscow-backed Eurasian Customs Union.

Most controversial was Mikoyan’s participation in the 1930s Stalinist Terror in Armenia. Why, some wonder, would anyone build a monument to a man who carried out Stalin’s orders?

At the same time, the Mikoyan statue project does have its supporters. They point to Mikoyan as a statesman in the post-Stalinist era and speak about his role in working to defuse the Cuban Missile Crisis. Others look favorably on his brother, Artyom, for his work on the Soviet MiG aircraft; and there have also been proposals for statues of both Mikoyans in Yerevan.

So, who was this Mikoyan and why is he so controversial in Armenia?

While basic narratives, focusing on the statue issue, attempt to cast Mikoyan as a Stalinist henchman, in reality he is a far more complex historical figure. Certainly he was involved in the Stalin-era Purges, both in Armenia and in Russia. At the same time, Mikoyan was also an enthusiastic supporter of the NEP, a notable opponent of the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary, and the man who played a key role in defusing the Cuban Missile Crisis. Most significantly however, it was Mikoyan who, together with Khrushchev, led the effort toward de-Stalinization, who actively worked to rehabilitate Gulag victims, and who helped form the environment for the Khrushchev-era Thaw. Thus it was Mikoyan who helped to pave the way for greater democracy and civil society in the former Soviet space. It is this complex and multifaceted portrait of Mikoyan that I shall present to the readers of this publication in order that they attain a more complete understanding of this historical figure beyond one-dimensional debates.

From Sanahin to Stalin

Born in Sanahin in Armenia’s northern Lori province in 1895, Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan was an Old Bolshevik and a constant survivor “from Ilyich [Lenin] to Ilyich [Brezhnev].” Indeed, time after time, Mikoyan somehow always managed to very narrowly escape death. He was among the Baku Commissars who were arrested by the British and executed in Turkmenistan. Yet, unlike the 26 who were actually shot, Mikoyan somehow miraculously managed to escape. He also survived the worst of the Stalin years and, after World War II, appeared to be a prime candidate in a potential second Stalinist Great Terror. Only Stalin’s death in 1953 saved Mikoyan from such a fate. Finally, despite his close association with Nikita Khrushchev, Mikoyan also managed to survive the “soft coup” against that Soviet leader in 1964, in which Brezhnev and his clique assumed power. After this, Mikoyan assumed the position of the nominal Soviet head of state. However, this would prove to be short-lived. In 1965, he was forced to retire and spent the rest of his life writing his memoirs until his death in 1978.

Hailed as the “Armenian wheeler-dealer,” Mikoyan’s penchant for survival made him something of a legend in Soviet times. A common anecdote was that Mikoyan was visiting friends when a thunderstorm broke out. Mikoyan rises from his seat, gets his hat and coat, and says, “well, comrades, it looks like I have to go.” But his hosts protest. “No, Anastas Ivanovich! You can’t go now! It’s pouring rain outside!” Mikoyan smiles. “It’s okay. Don’t worry! I can dodge between the raindrops!”

Mikoyan was educated at the Armenian Orthodox Nersisyan Theological seminary in Tiflis (Tbilisi), Georgia and at the Gevorkian Theological Seminary in Etchmiadzin. However, young Anastas turned away from Armenian Orthodoxy and instead eventually embraced the materialist revolutionary ideas of socialism, Marx, and Engels. One of his closest friends and fellow classmates was Georg Alikanyan, the future father of Yelena Bonner, the human right activist, dissident, and wife of fellow dissident and nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov.

After the revolution and the civil war, which included Mikoyan’s participation in the Baku commune and his legendary escape from execution, Mikoyan went to Moscow. It was here where he began to forge close links with Stalin, who saw a potential political ally in Mikoyan, due to their shared roots in the Caucasus. Subsequently, on Stalin’s recommendation, he was appointed secretary of the Southeastern Bureau of the Central Committee. He soon ran the Northern Caucasus Regional Committee for the party. It was here that Mikoyan proved to be a competent and effective administrator. He advocated an open and lenient policy toward the Cossacks and other tribesmen who were opposed to Soviet rule. He allowed them to maintain their unique way of life and traditions. He even encouraged the Cossacks to engage in their traditional horsemanship and integrated them into regional units of the Red Army. He also worked to bring the peasants, the Cossacks, and the tribesmen closer together and to discourage animosity. All of these policies were very successful and were assisted by the advancement of Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP), a mixture of socialism and capitalism, intended to put the country back on its feet.

Left to right: Anastas Mikoyan, Joseph Stalin, and Sergo Ordzhonikidze

Between his success in the North Caucasus and the links that he forged with Stalin, Mikoyan was able to maneuver his way to the position of People’s Commissar of External and Internal Trade in 1926. At the age of 30, Mikoyan was the youngest member of the Politburo. It was in this position that Mikoyan made his career. In the 1920s, Mikoyan initially favored the NEP, whose positive results he saw first-hand during his time in the North Caucasus. According to his son, Sergo, Mikoyan was “so impressed by the possibilities opened by NEP that he argued with Stalin openly at the Fifteenth Party Congress in 1927, and at other meetings, Mikoyan spoke in favor of trade as the key to getting grain from the village.” According to the Soviet historian and dissident Roy Medvedev, Mikoyan also stood “firmly opposed to the severe treatment of the individual peasant farmers and kulaks.” At the 15th Party Congress, he advocated moving forward “in the most painless way,” disagreeing with Stalin who advocated for harsher measures. He ultimately disagreed with Stalin’s policy of forced collectivization, but was careful not go so far as to break with the vozhd.

By the early 1930s, the country had entered into an economic crisis. Stalin’s policies proved disastrous, especially in the cereal, wheat, and grain-producing “breadbaskets” of Ukraine, the North Caucasus and Northern Kazakhstan. Forced requisitioning created famine conditions. Many citizens died of starvation. The country was in an economic mess and the new situation also required that the Trade Commissariat, which Mikoyan headed, be changed as well. Neither the name nor the methods corresponded with the reality on the ground, and thus the Commissariat was reformed into the People’s Commissariat of Supply. Yet to many Soviet citizens, supply was very marginal and a black joke began to circulate: “We’ve got no meat, no milk, no butter, no flour, no soap, but we’ve got Mikoyan.” (“Нет мяса, нет масла, нет молока, нет муки, нет мыла, но зато есть Микоян.”).

“At the beginning of the first Five-Year Plan,” wrote the historian Roy Medvedev, “there was an acute shortage of hard currency in the country.” The Soviet government sought to gain such currency through the sale of priceless art treasures and artifacts from the Hermitage Museum and from the Tsar’s personal collection which had been confiscated by the Bolsheviks. These sales were staunchly opposed by Commissar of Education Anatoly Lunacharsky and others who were ultimately overruled by the Politburo. Mikoyan was tasked with heading this commercial venture.

At first the sale was difficult. White Russian émigrés and former aristocracy abroad led the charge in opposing and/or disrupting such sales. As such, there was little success in major émigré centers like France and Germany. Instead, Mikoyan concluded his first big success with the Armenian businessman and philanthropist Calouste Gulbenkian, famously known as “Mr. Five Percent.” There were also substantial sales from the United States, especially from former US Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon. Most of these works are now housed in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Overall, these sales managed to yield about $100 million for the Soviet Union.

In his capacity as the Commissar of Supply, Mikoyan also sought to import Western ideas into the Soviet Union. He traveled to the United States and brought back the innovation of canned foods. He studied the American food industry, investigated Macy’s in New York, and chatted with US Secretary of State Cordell Hull and the industrialist Henry Ford. In the Soviet market, he introduced ice cream, hamburgers, popcorn, cornflakes, and more. He also increased the number of beefsteaks into the Soviet Union. Today, in many former Soviet countries, the best steaks and chops are still called “Mikoyans.” Mikoyan also sought to curb the consumption of vodka, yielding some impressive results, and also introduced the first cookbook in the Soviet Union called The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food (Книга о вкусной и здоровой пище). Mikoyan continued his duties into the war when he directed the supply of food and provisions to Red Army troops. For the latter service, he was rewarded Hero of Socialist Labor in 1943. Also during the war, Mikoyan’s 18-year-old son, Vladimir, a fighter pilot, died in Stalingrad when his plane was shot down by the Germans.

The Purges

The question of Mikoyan’s role in Stalin’s Terror has stimulated much debate in Armenian society. According to Medvedev, Mikoyan was coerced and threatened to participate in the Terror by none other than Stalin himself who perceived Mikoyan as being “too soft” and “too lenient.” In his book All Stalin’s Men, he writes:

People’s Commissars had to sanction the arrest of leading members of their own staff, so it is difficult to believe that Mikoyan knew nothing about the repression of many of the top personnel in the food industry and in commerce. By contrast, G. K. Orzhonikidze, who had tried to protect his staff, was driven to suicide in early 1937. He had been a friend of Mikoyan, who named the youngest of his five sons, Sergo, after him. Twenty years later, speaking at the Red Proletarian Factory, Mikoyan told the story of how Stalin had summoned him after Orzhonikidze’s death, and had said, threateningly: ‘That story of the shooting of the twenty-six Baku Commissars and how one of them, you, managed to stay alive – it’s all pretty vague and confused. And you’ve never wanted us to try and clear it up, have you, Anastas Ivanovich?”

Living under constant threat that he might be accused of betraying his comrades in the Baku commune, even Ordzhonikidze’s solution was not an option for Mikoyan. So he submitted to Stalin.

Among his assignments, Mikoyan was made chair of the Stalin-appointed commission that ultimately doomed Nikolai Bukharin and Aleksei Rykov. Both Rykov and especially Bukharin were strong proponents of the NEP in the Soviet Union. Stalin considered both a threat to his power. The fact that Mikoyan, once a supporter of the NEP and a friend to both men, chaired the commission was ironic. According to Roy Medvedev, the terms of reference of the commission were “brief and to the point: ‘Arrest. Try. Shoot.'”

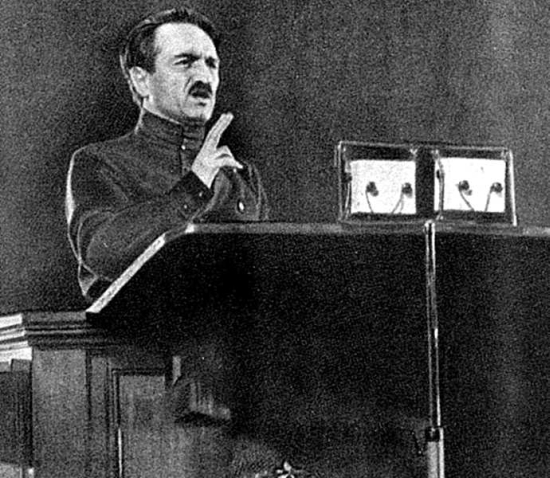

Mikoyan Giving a Speech, 1930s

Further, Mikoyan, like Khrushchev, made speeches about the fight against supposed “enemies.” Mikoyan represented the Politburo at the 20th anniversary ceremonies of the NKVD. In his speech, he condemned “enemies of the people” and praised NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov for his “Stalin way of work” and for creating a “wonderful backbone of Chekists” that were “trained in true Bolshevik manner in the spirit of Dzerzhinsky.” In reality, Mikoyan had a less-than-positive attitude of Yezhov.

It was also Mikoyan who, along with others in the Politburo, signed Stalin’s orders on arrests, executions, and deportations. These included lists composed by Yezhov of supposed “enemies” to be shot. They also included the order to execute the Polish officers at Katyń and on the wholesale deportation orders of various nationalities such as Chechens, Crimean Tatars, Germans, and others. However, according to an Ossetian émigré cited by Medvedev, Mikoyan was the only one of Stalin’s ministers who expressed misgivings about at least the Chechen and Ingush deportations. In general, while Mikoyan may not have agreed with such orders, he really had no choice. The act of vocally opposing such policies would have had serious consequences in Stalin’s Soviet Union, not just for him, but for his entire family and all of his relatives too. Indeed, the threat was real. During the war, in addition to the death of his son Vladimir, Mikoyan experienced another brief tragedy in his family when two of his sons, Sergo and Vano, were arrested on the orders of Stalin for playing a children’s game of “government.” They were exiled and not returned to the Mikoyan family until after the war.

Mikoyan was also dispatched to his native Armenia with Malenkov in September 1937 to oversee the Purges there. The Soviet Armenian republic’s newspaper Kommunist wrote at the end of 1937 that, “Comrade Mikoyan rendered a great service to the Bolsheviks of Armenia” on the orders of “Great Stalin” by “unmasking and rooting out the enemies of the Armenian people,” a “cabal” of “Trotskyist-Bukharinist, Dashnak-Nationalist spies.” It should be noted though that the Purges in Armenia were already well underway by the time of Mikoyan’s arrival. In the words of the noted scholar on Soviet Armenia, Mary K. Matossian, in her book The Impact of Soviet Policies in Armenia:

From the foregoing it would appear that Mikoyan was a mere agent of Stalin and Beria in the Great Purge, although he appears as a leading protagonist in the culminating events of September, 1937. But it may also be observed that Mikoyan is not directly implicated in the death of [Aghasi] Khanchian or of [Sahak] Ter-Gabrielian. On the contrary, he appears in the role of the purger of Amatouni, who had denounced Khanchian, and of Moughdousi, who is said to have killed Ter-Gabrielian. Further, if Mikoyan had a personal following, there is no evidence that any members of such a following became heirs to power in Armenia. It may be concluded that Mikoyan cannot be disassociated from the guilt of the Great Purge, but that his role in it was relatively minor.

Additionally, Mikoyan also sought to save as many people as he could, both inside and outside of Armenia. These included people who had not yet been arrested as well as friends and family members of those who already had. Among those that Mikoyan saved was the future hero of World War II, Ivan Bagramyan. He was a student at the Staff Academy in 1937, a time when, in Medvedev’s words, “a campaign of denunciation was raging there and super-vigilance was the order of the day.” Eventually, Bagramyan was accused of being a “Dashnak agent.” On the advice of his friend, the military commander and future dissident Pyotr Grigorenko, Bagramyan wrote to Mikoyan. Ultimately, it was Mikoyan who intervened to save Bagramyan from arrest.

Another case was of Aleksei Snegov, a Communist Party official from Ukraine and a friend of Mikoyan’s whom the dreaded Lavrentiy Beria despised. Snegov was arrested in Leningrad in 1937, cruelly tortured and sentenced to be shot. All of Snegov’s so-called “accomplices” in the trumped-up show trial had already been summarily executed. Yet, suddenly, Snegov was spared, his charges were dropped, and he was rehabilitated. Nikolai Yezhov, the sadistic chief of the NKVD who directed the worst of the Purges, had been dismissed. He left Leningrad for Moscow where he called upon Mikoyan. When he told Mikoyan that Zarkovsky, the head of the Leningrad NKVD had been shot, Mikoyan reportedly remarked “one swine the less.” He was also sad when he heard of the suicide of Litvin, a Party worker who was posted to the NKVD but shot himself and left a letter indicating his refusal to participate in the Purges. Snegov then told Mikoyan of his plans to go to the Party Control Commission to report his detainment. Mikoyan immediately advised him against such a move. Instead, he gave him a permit for a holiday and some spending money. But Snegov insisted and so Mikoyan grudgingly phoned Shkiryatov, the head of the Control Commission, to investigate Snegov’s case and to settle it. Shkiryatov, an associate of Beria, expressed “concern” and asked Snegov to head to the Control Commission headquarters. He did so, was asked to wait in the lobby, and in less than half-an-hour was arrested by four NKVD men. Snegov spent the next 14 years in a Gulag concentration camp.

Khruschev and Mikoyan

De-Stalinization and the Thaw

Following Stalin’s death, Mikoyan soon emerged as a close associate of Nikita Khrushchev. Like Khrushchev, he actively sought repentance for his involvement in Stalin’s crimes. It was Mikoyan who persuaded Khrushchev to give his famous “secret speech” against Stalinism at the 20th Party Congress of the Soviet Communist Party.

More significantly, supporting Khrushchev and Mikoyan in their endeavors were individuals like Snegov and other former Gulag prisoners like Olga Shatunovskaya and Valentina Pikina. Upon their release from the camps in the 1950s, these former Gulag inmates, nicknamed Khrushchev’s “zeks” (a Russian slang for “inmate”), persuaded Mikoyan and Khrushchev to begin a de-Stalinization initiative and to order the release of all remaining political prisoners. According to Russian and Soviet scholar Stephen F. Cohen in his book The Victims of Return, “in private discussions and written communications, Shatunovskaya and Snegov ‘opened the eyes’ of Khrushchev and Mikoyan, as the sons of both leaders later confirmed, to the full dimension and horrors of the terror.”

Khrushchev and Mikoyan actively sought de-Stalinization and repentance for their involvement in Stalin’s crimes. By contrast, others who served under the vozhd – such as Molotov, Kaganovich, Voroshilov, and Malenkov – remained totally unremorseful for what they had done and even attempted to scuttle the de-Stalinizing efforts of Khrushchev and Mikoyan.

Mikoyan and Family

Indeed, Mikoyan not only supported and encouraged Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization endeavors, but also began many of his own. For example, at the 20th Party Congress, prior to Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization speech, Mikoyan delivered an address the crowd, exonerating victims of the Gulag and Stalin’s Terror and mentioning them by name. Additionally, according to Roy Medvedev, after the 20th Party Congress, “Mikoyan organized about a hundred commissions whose remit was to visit all the labour camps and other places of detention and to carry out a rapid review of the charges against all political prisoners.”

In a personal capacity, Mikoyan actively sought to help and support victims of Stalinism, intervening on their behalf. These included Bulat Okudzhava and his mother (a returnee from the camps), the families of Bukharin and Rykov, and a young Yelena Bonner who, it may be recalled, was the daughter of Mikoyan’s old friend, Alikanyan. He also worked actively to help rehabilitate many of these victims and even worked to give a pension and apartment to Mikhail Yaubovich, a homeless and destitute returnee. Mikoyan made personal visits to the families of victims, including to Yuri Larin, the son of Bukharin. Mikoyan had been a good friend of Bukharin’s but, at the same time, had also been tasked by Stalin to chair the commission that was ultimately responsible for his purging. Such significant meetings, in the words of Stephen Cohen, “suggested a need for absolution.” On the cultural front too, Mikoyan assisted Khrushchev on de-Stalinization and extended crucial support in, for example, the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Mikoyan’s efforts toward de-Stalinization were also not only limited to Russia and the “center,” but also extended to his native Armenia as well. In 1954, he traveled to Yerevan and delivered a speech. Speaking to the crowd in Armenian, he declared that the Communist Party of Armenia had been greatly mistaken for purging the “talented Armenian poet” Yeghishe Charents, a victim of Stalin’s Terror who was shot in 1937 for “counterrevolutionary” and “nationalist” activity. Instead, Mikoyan now told his audience that Charents’ works were “outstanding in their great talent” and were “steeped with revolutionary pathos and Soviet patriotism” that “must become the property of the Soviet reader.” In his speech Mikoyan also exonerated the poet Rafael Patkanyan and the revolutionary writer Raffi:

Of course there are nationalist shadings in some of the works of Patkanyan and Raffi, but on the basis of this can we renounce a cultural inheritance which reflects several pages of the heroic struggle of the Armenian people against Turkish and Persian enslavers, which glories with love and high feeling the life and work of the people?

The Soviet Armenian leadership took their cues from Mikoyan, rehabilitating and republishing writers who had died in Stalin’s Purges including not just Charents but others as well like Aksel Bakunts whose work was praised for its “heroic, freedom-loving spirit.” A ten-volume edition of Raffi’s works was set to print. At the 20th Party Congress in Moscow, Soviet Armenian leader Suren Tovmasyan gave a speech in praise of the works of Charents.

Sergo Mikoyan

Yet despite this liberalization in Armenia, many Armenians to this day believe that Mikoyan could have done more with regard to the disputed region of Nagorny Karabakh. Once the center of the historic Armenian province and principality of Artsakh, the majority of the population of this mountainous territory are ethnic Armenians who speak their own unique colorful dialect of the Armenian language. Armenian churches and cultural monuments can also be found throughout the area. Despite this, the region was assigned to Soviet Azerbaijan during Sovietization. The Karabakh Armenians never accepted this decision and protested periodically. In 1964, the Armenians of Karabakh sent a petition to Khrushchev demanding unification with Soviet Armenia. This appeal was left unanswered and it is unclear whether or not Khrushchev (let alone Mikoyan) ever even received the letter. It is likely that had Mikoyan lived long enough to see glasnost, he would have supported the demands of the Karabakh Armenians, especially since his son, Sergo, was a major advocate for the unification of Karabakh with Armenia starting as early as 1987. Speaking to an Armenian-American newspaper at the time, Sergo said:

I think that it’s now much more realistic to demand the return of Karabakh to Armenia. And I think it’s only now, during perestroika, that we may not only speak about it, but have very strong hopes that it will be done.

Mikoyan, Khrushchev, and Che Guevara

In the Thaw era, Mikoyan also earned a notable reputation for working to resolve issues without the use of force. For example, with the rehabilitation and the return of the Chechens and Ingushi to their native lands, Mikoyan tried to prevent conflict between them and the local Russians who had come to the region during the Stalin years. In 1956, Mikoyan stood against Khrushchev’s decision to send tanks into Hungary to crush the revolution there, warning that it would be a “terrible mistake.” Finally, in Novocherkassk, Mikoyan worked to prevent bloodshed, claiming that he “had thought it feasible to arrange talks with workers’ representatives.” According to him, the hardliner Mikhail Suslov, who was also there at the time, was to blame for the subsequent violence.

In 1957, Mikoyan remained loyal to Khrushchev by refusing to go along with the attempted Malenkov-Molotov coup against him. In foreign relations, Mikoyan is still warmly remembered by many Americans for his surprise high-level visit to the United States in 1959 where he opened the Soviet exhibition in New York and met with businessmen like Averell Harriman and John J. McCloy. From here he traveled to other parts of the country. In Washington, he met President Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. In Cleveland, he visited another business leader, Cyrus Eaton and admired the city skyline with Cleveland’s Terminal Tower reminding him of the Lomonosov State University in Moscow. In Detroit, he held conversations in Armenian with a local Armenian-American. In less positive visits to Chicago and Los Angeles, he was met by protestors which Mikoyan just shrugged off with sarcasm and humor. He also stopped by San Francisco and Hollywood and met the stars there, including Sophia Loren and Jerry Lewis.

Mikoyan and Castro

That same year, Mikoyan also paid a very important visit to Cuba and fell in love with the island. On Castro, he wrote to Moscow, “Yes, he is a revolutionary. Completely like us. I felt as though I had returned to my childhood.” Moscow now had a new ally in post-revolutionary Havana, and Mikoyan quickly became Khrushchev’s go-to man for information on the island. Then Khrushchev had an idea about which he consulted Mikoyan. Khrushchev proposed placing missiles on the island which he believed the US would accept calmly and, in return remove their missiles from Turkey. Mikoyan doubted that Washington would receive the news calmly and feared that it would lead to a crisis. Khrushchev claimed later that he saw the dangers too, but proceeded anyway. As the historian William Taubman notes, he might have also solicited second opinions from others as well, such as Anatoly Dobrynin and Oleg Troyanovsky. However, the plan proceeded and the infamous Cuban Missile Crisis ensued.

Mikoyan and his wife, Ashkhen

Most Americans are quick to recall that the crisis ended when Khrushchev withdrew the missiles from Cuba and that later it was revealed that this was in exchange for the removal of US missiles from Turkey. However, for Moscow, a “second crisis” ensued shortly after this in which Castro, feeling like a pawn on the superpower chessboard, refused to give the missiles back to the Soviet Union. It was up to Mikoyan to go to Cuba to persuade the Cuban revolutionary to give up the missiles, which eventually followed. As the negotiations began, Mikoyan was informed of the death of his wife, Ashkhen. However, the crisis was too pressing. He was the USSR’s chief expert on Cuba and could not abandon the negotiations. He had to miss his wife’s funeral and sent his son Sergo instead. Had Mikoyan not been present to persuade Castro to remove the missiles at that time, the larger Cuban Missile Crisis would have continued.

This “crisis with Castro” was the subject of a recently published book entitled The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November based on new, revealing research. It was authored by Mikoyan’s son, Sergo, who went on to become a leading academic authority of Latin America in the Soviet Union and, after 1991, Russia. Notably, in a 2006 article in the Russian newspaper Izvestiya, Sergo Mikoyan compared Georgia’s President Mikhail Saakashvili to Cuba’s Castro, calling Saakashvili the “American Castro.”

Mikoyan remained loyal to Khrushchev into the 1960s and Khruschev even conferred with him on the possibility of reforming the Politburo entirely into a new “socialist parliament.” Mikoyan was impressed with the idea, but times were changing and Mikoyan could sense a shift in the balance of power. He ultimately decided to side with the Brezhnev’s “soft coup” in 1964, though he himself was not one of the coup plotters. He gained the position of the nominal Soviet head of state but this did not last long. He was forced to retire in 1965, returned to private life, wrote his memoirs, and passed away in 1978.

Given this entire historical overview of Mikoyan, the debate over Mikoyan’s legacy remains. The statue controversy is just the latest episode. However, understanding the realities of Mikoyan is critical to any debate about him. While it is true that he was an accomplice in Stalin’s Purges, his entire legacy as an individual should not be limited to this, especially given his role in defusing the Cuban Missile Crisis and given that he made the very heroic and courageous decision to support and encourage Khrushchev in his major de-Stalinization efforts.

It was these efforts that paved the way for the development of civil society and democracy in the former Soviet space today. Mikoyan played a significant role in this development. When both sides of this complex man are identified, will his legacy be one of terror or of repentance and reform?